643% increase in health services traffic. 1992% increase in pharmacy visits. These are the results of my CVS Search transformation—turning a basic drug store item finder into a comprehensive health discovery platform across 5 vendor systems.

Setting the Stage

Problem

Our problems were two fold. From the user's point of view, CVS search only included retail products- vitamins, toiletries, and OTC Medications. This does not represent a true CVS search, as our site offers pharmacy services, MinuteClinic appointments, drug information, health articles and photo services. Most users weren't even aware CVS offered these services. From a business perspective, we were missing massive opportunities.

Challenge

Design problems were only half the battle. My product partners were hesitant to risk affecting the revenue-generating search experience with any large design change, so alignment took time. While designers typically work on predetermined features, this project required advocating for a completely new strategic direction.

When I first joined the On Site Search team, my assignments were piecemeal additions to retail search - logical for a retail-focused team, but I could see the transformative potential.

As we advocated for including more connections within search, our business stakeholders received the directive from executive leadership that the company needs to focus on and start promoting its health services. This opened the door for us to include specific minute clinic service suggestions in relevant search queries. The results were clearly impactful MinuteClinic immediately saw a substantial boost in traffic, roughly 30%. No marketing, no promotion, no annoying pop ups about new features. Just good design.

This became our playbook: small design changes → immediate measurable impact → leadership buy-in → full transformation → 600%+ growth in health services traffic.

Discovery & Research

User Testing

Throughout this project there were several rounds of user testing at key intervals. Our very first stage of user research, usability testing on including MinuteClinic links in search suggestions, was a success. This helped prove the viability of unifying the various search experiences across the CVS web platform to our stakeholders and leadership.

Thanks to this small step towards a broader search, we were able to understand user expectations regarding the relationship between search and navigation. This facilitated a smoother approach to a expanded search across multiple databases and lines of business. The challenge was not the UI, as evidenced by consistent strong user feedback (with the exception of one project mentioned later). That's not to say there were no challenges, but we were confident in our ability to 'connect the dots'. Where exactly were all our dots were was an entirely different question.

To start on some more low/medium fidelity concepts, we began looking at competitors. Usually in eCommerce focused search team, we examine competitors like Walmart, Costco, Home Depot, Target and other large retailers. However, we found that despite some of these retailers offering expanded services, even similar to ours, their searches were focused exclusively to products in all cases. At the time of our research, the only competitor in the retail space who featured any non products in search were amazon search results including call outs to pharmacy services and similar content.While some sites like Houzz featured scoped suggestions, and BlackRock displayed segmented results, no competitor was combining these patterns in a truly multi-database search. In short, we had a massive opportunity to fill a gap all of our competitors had.

In any sense, one thing was clear, no competitor was doing all of these things at once. We felt that every competitor, at best, had a robust search results or search suggestion state, but no one had both. In fact, our closest competitors were, like ourselves, still only returning results for products. There were massive opportunities to build a new type of search, inspired by the sites doing unique things, that could connect users to all segments of a site in an intuitive and accessible way.

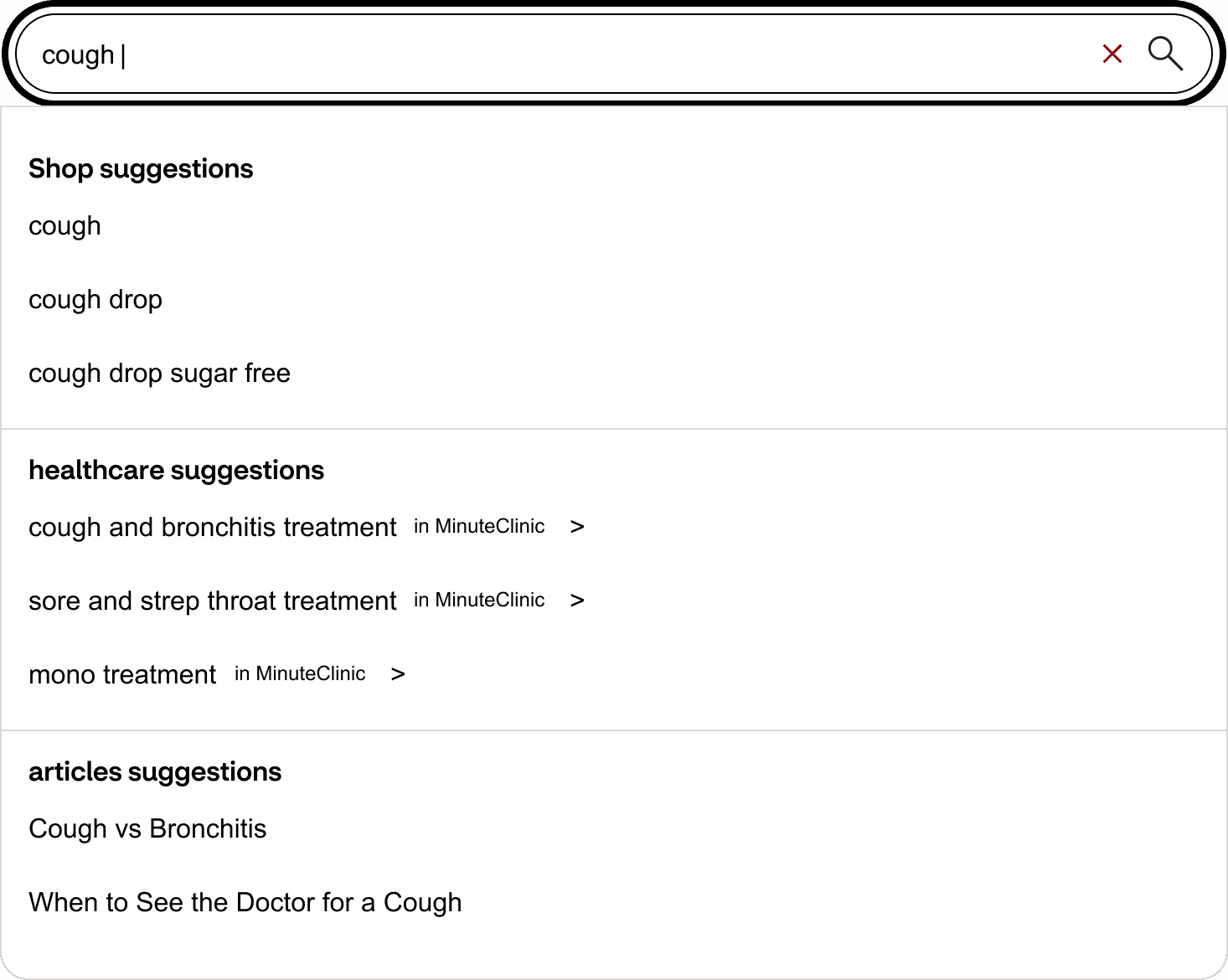

Data Science Collaboration

A unique responsibility of this project was establishing “buckets of search” with our product team. These would serve as the guidelines for our later UI work- segmenting buckets of search using clean patterns and clever copy. Part of the work on establishing these buckets was collaborating with our data science team to understand what we data we had access too, what kinds of data each bucket of search might have, and refine our approach where necessary.

These conversations were successful but not without friction. As mentioned previously, photo took some extra work. This was an instance where data science was helpful, as it was easier to understand how the photo data was tagged thanks to several Data Science partners walking me through it, as opposed to trying to reverse engineer that info through their web experience. As mentioned previously, our solution was pretty clean without solving all of photos problems because that was simply out of scope.

In other instances, this team provided more friction than we'd like. I can't speak for why, but our data science partners had a lot of opinions on what the UI should look like and what the UX should be. Unsurprisingly, their approach was very technical and not the most user friendly, although impressive. Ultimately, thanks to backing from product, design leadership, and armed with user data, we were able to push back on these opinions, as they conflicted with our user research. Part of the super app approach was being “user feedback driven” so ultimately we were able to get our solution out the door.

Strategy & Approach

Building the Business Case

As mentioned earlier, there was an executive mandate to focus more on healthcare offerings, as the MinuteClinic business continued to expand and show promise. Cvs also made significant acquisitions like Oak Street Health and Signify Health to bolster clinic operations.

With these acquisitions, several other key factors led to this healthcare push. Leadership desired a SuperApp so that users can not only buy their vitamins and makeup online, but also schedule vaccination refills, deliveries and transfers, schedule healthcare appointments and tests, print photos and learn about health and wellness from a trusted source. Some of these services were already available, but getting them in front of users was a challenge. When you offer so much, how do you help users make sense of it all?

Learning from Early Attempts

Prior to our search team existing on the super app train, it was part of the retail train. Within this train, a separate team owned the page that search results lived on. This complicated and frankly, restrained, the impact we could have on the search results page. Any changes we wanted to make meant dealing with another design and product team, and often times were met with more friction than ultimately necessary.

My product partners heard my ideas, and thanks to aligning business interests, we wanted to test an initial step towards an expanded search. We already tested and released MinuteClinic additions to the search box. One of my core search philosophies is that search suggestions and results should be mapped to one another. Search suggestions and results should feel related, like two sides of the same coin. If i'm seeing search suggestions organized one way, I expect to see the results organized in a similar fashion. As such, we wanted to organize search results into two sections, health results and product results. A new page was not on the table, so as a compromise I wanted to include a link to the MinuteClinic homepage on related searches carefully wedged in between rows of the product grid. This is not an ideal place, but it's commonly used for CMS (ads). To use it for a helpful related link felt like the most intuitive and appropriate way to accomplish what the business needed, but the team that owned the page wanted us to not break the grid and use cards.

After a reorg and the creation of the Super App Train, we no longer were bound by this team. Search would own search results, and the product grid would just be one part of that multifaceted system. This was something myself and partner had been pushing for, and product was receptive. So this problem solved itself, but I believe we wouldn't have been given this ownership had we not demonstrated a clear forward thinking vision.

Organizational Shifts Created Opportunity

As mentioned previously, there were organizational challenges involved in implementing our search vision. Due to our parent organization's focus on retail products, a team with a lot of clout owned the results page separate from search. This team owned the 'product listing page' and as such their top priority was the items on the product grid, and the conversion rate of customers on that page.

This all makes perfect sense, and it is true that messing with a successful product grid is generally ill advised. However, due to the fact that our team did not own this page, we were not enabled to do exploratory work. There was also apprehension about creating any additional steps or pages between where typing and the search results grid, as again, harming conversion was a huge risk to stakeholders.

As part of the Reorganization that focused on health, CVS created the SuperApp team. This reorganization was not about punishing retail or deprioritizing it. Rather, it was about allowing health services and information as easy to find as products. It was about including them in the search experience, where they always belonged. As such, this reorg meant that we owned the search experience in full. Leadership's priorities now aligned with our vision, which was that Search should connect Customers to a sites offerings, not a small section. We now were able to explore how best to include all these connections in a seamless experience.

Incremental Wins Strategy

As stated previously, the changing business environment eventually enabled our search expansion. It did not happen over night, nor in a vacuum. When I first joined and our search team was still retail focused, our main strategy was incremental wins. We also wanted to ensure that our concepts were sound.

Following the executive healthcare directive, our product partners wanted us to include MinuteClinic services on the initial search view, or the search drop down that users see before they stop typing.Whether you searched for toothpaste or diabetic test strips, you would see MinuteClinic. As search priorities slowly began to include health care services, our first feature was including our most popular/profitable minute clinic services in search. Design advocated for including relevant minute clinic services, the top 25 chosen by our stakeholders, included amongst search suggestions.

This 30% boost proved our strategy worked: small design changes could drive immediate measurable impact, earn leadership buy-in, and enable full transformation that ultimately delivered 600% growth in health services traffic.The result was a 30% boost to MinuteClinic services compared to the 90-day period prior to launch.

It's important to remember that search can't include too much, its a highly focused, task driven section of the site. MinuteClinic was the first healthcare focused addition to the search box I worked on, but there were plenty of retail enhancements I made during this time period as well. We included a number of search view and typeahead features that were retail focused, and we had to reconsider how these fit into the equation with the added weight of MinuteClinic links.

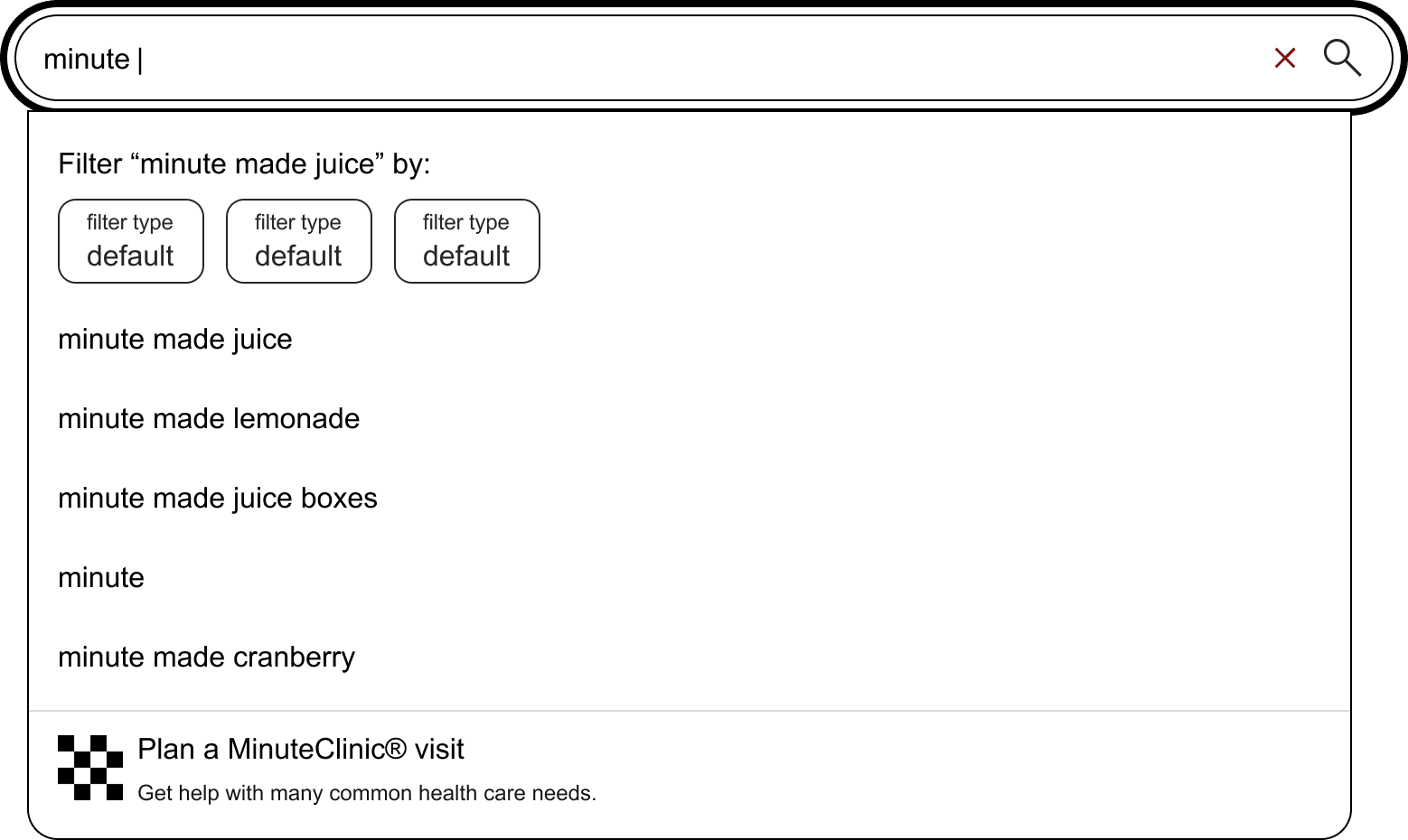

Some features that we had to be careful about were our retail quick filters [PHOTO]. These filters make sense in the context of retail search. Filters being included amongst expanded search suggestions, where they only apply to a portion of the potential search results, does not make much sense. After demonstrating what this experience would feel like with a quick prototype, our product partners agreed. Our new quick filter logic was that quick filters would appear only when search suggestions were retail focused. In other words, if I am getting search suggestions for any non-retail sections, I won't see quick filters. Recently viewed items was a similar situation. We had to pause including it until we could do more testing and observe search performance, as we wanted to carefully consider every part of the existing and new search experience and how they'd fit together.

Cross-Team Collaboration

While I designed the expanded search typeahead experience, my partner worked on the expanded search results. Our primary focus was making sure that results and typeahead alike function as one cohesive system. Search is an organism - typeahead and results are vital organs that must work in harmony.

Our plan was for typeahead to set the tone, given a few compelling reasons. Chiefly, that work had design concepts that tested well previously, giving us a good foundation to hit the ground running. Our product team had therefore prioritized this feature first. My partner and I met regularly to ensure that suggestions, scoped searches, and the like were presented in ways that aligned with user expectations. For instance, our results needed to be segmented in the same logic that our typeahead was using. The suggestions needed to be mapped to the results. This meant stress testing, finding odd bits of data that we could treat as use cases (e.g. long names) and creating quick and dirty prototypes to see how it would feel moving through the experience.

Beyond our designer partnership, we also had to work with several vendors. The CVS Photo vendor's platform had significant usability and information architecture limitations that created design constraints. Our retail search was originally handled by an outside vendor as well, so I had experience collaborating with external search vendors. That's not to say it was easy; working with external vendors meant navigating platform limitations, clarifying requirements through multiple touchpoints, and ensuring CVS design standards were maintained within third-party constraints. That's all without the budgetary conversations. Many of our vendors were replaced by in-house platform teams after continuous platform constraints and budget inefficiencies became clear. Design consistently advocated for in-house solutions throughout this process. Some vendors like photo remained external, but the transition to in-house teams significantly improved our ability to iterate and maintain design standards.

Design Process

Multi-Database Search Patterns

Building a search that connects CVS' offerings means pulling from multiple databases. Each one of these databases is managed by different teams, and that brings a lot of complexity. At such a large company, we were dealing with multiple code bases, different vendors, and systems that didn't follow our established search patterns.

We had to work to understand the current MinuteClinic, Photo, Pharmacy and Wellness Zone experiences from a user and technical perspective. For example, we had to resolve complex overlaps such as distinguishing pharmacy vaccine services from MinuteClinic vaccination appointments. This required clear logic so users wouldn't be confused about which service to choose for their specific needs. Not every CVS has a MinuteClinic, but vaccines are still available in most stores throug the pharmacy. Meeting with these teams involved bringing our product and development partners along; poking, prodding, and asking a lot of questions. We also often would sketch together ideas as they came up.

Thanks to all this collaboration and coordination, we were able to understand the data sets and user-flows of each search experience. It would be an impossible task to design an elegant search solution that maintained each business units' flow, much less preserving their busy and outdated UI patterns. These sessions were crucial to understanding the relationship between search, data, and the users. We then consolidated the data in order to allow users to search these business units in a clean and predictable way.

Findability and Browsability: A Search Philosophy

Armed with my research, I positioned this project as capitalizing on an existing gap in the market. Our key differentiator would be combining scoped suggestions with direct links in a simple, accessible interface. Users could connect with products, content, and services directly, bypassing results pages entirely when appropriate. Designing this experience required careful coordination across UI, content strategy, UX, and accessibility. We needed clear visual and programmatic differentiation between search suggestions and direct links for all users; that includes screen reader users. Most crucially, these interface affordances needed to ensure user expectations aligned with their actual destinations.

We validated that users expectations aligned with our experience by running unmoderated user testing with over 100 participants. This was a mix of folks somewhat familiar with CVS, and loyal CVS customers. We also made sure to select very broad demographics to ensure we could cast a wide net, simulating our actual customer base. What we found validated our assumptions: users want to both browse and find information. We assist users who already know what they're looking for with direct link and scoped search. For users who want to see more results and browse, they can select suggestions, moving to a results page where they can easily move between scoped results.

The results validated our core assumption: users want to both browse and find information through different pathways - a stark contrast to the one-size-fits-all search approach used by competitors.

Keeping What Works

While my new search experience was going to be transformative, we did not want to reinvent the wheel. In a paradoxical way, a search that pulls together complex databases needs to be intuitive and simple. We already had existing user research that validated our list approach, so we kept this pattern as it worked incredibly well at scale with out too much of a fuss.

We also wanted to keep existing searchbox features that I had added back when we were tasked with only worrying about retail products. This includes retail search filters, in very specific scenarios. If a search term only returns results for shop, then a user can select dynamic quick filters prior to even ending up on the results screen, as per our search philosophy. Users who know what they want can get to it even faster now.

Managing Complex Stakeholder Dynamics

Managing relationships, feedback and changing priorities from stakeholders was its own design challenge. These conversations were at times challenging to keep focused, with lots of different people in the room. While we want to encourage ideas when we are doing collaborative working sessions, or discovery, at times our designs were met with unsolicited feedback. As an example, after testing our already data driven foundations, we presented these designs to our chief data science team that was working to build our new search back end. As our partners, we worked collaboratively to extract what design and data science needed from each team. As we had already had multiple collaborative sessions, we felt that the validated designs were ready to be annotated for hand off. In this session with the other teams that we were presenting our visions too, a VP from the Data Science team suggested an entirely different approach, that was frankly convoluted and not in line with user expectations. This was not appropriate timing or the appropriate venue, but we remained firm and pivoted to presenting more of our research findings than the designs themselves, to push back on the leadership interference. A bit awkward, but by the end of the meeting we had enough support to ship the designs.

Accessibility Leadership

I designed a select state for our searchbox, which preserved focus the component, while simultaneously allowing users to 'select' different search suggestions and list items. This enabled the search box to read out each new suggestion as something along the lines of 'Search for {{search suggestion}} in {{search category}}'. In the case where a user highlights a direct link, a screenreader would announce 'Go to {{direct link name}}'.

The select state paired very well with our list and text based approach, however this was not without scrutiny. Stakeholders, on the product side specifically, wanted to use iconography alone to communicate the various category of our scoped search. At CVS Health, we face extensive audits and from a compliance perspective, we had ways of doing this. For example, an ARIA label could be sufficient enough for a screen reader to announce the icons purpose and general appearance. This would be compliant. Despite this, I did not even test an icon only approach with our users. ARIA would be like a band-aid in this case, as a line of subtext describing the list items would not only be sufficient enough for a screenreader, it would also give sighted users way more context. Furthermore, there would be more parity for sighted and non sighted users, which is always my preference. Theres a difference between being merely compliant, and a good experience for humans across the board. I choose humans.

I am extremely thankful to have been educated by so many incredible a11y specialists at CVS Health, for I know that a greener version of myself would have let my users down in this department. It's unfortunately all too common for big companies to phone in accessibility, but our Search approach highlights a pleasant anomaly; We want our users to be able to take care of their health regardless of where they are in life. Our team also fostered an environment of learning and education, and our product partners did come around to our side. Thanks to some incredible teachers and business partners, I believe we created a transformative search experience that works well for more people than any of our competitors.

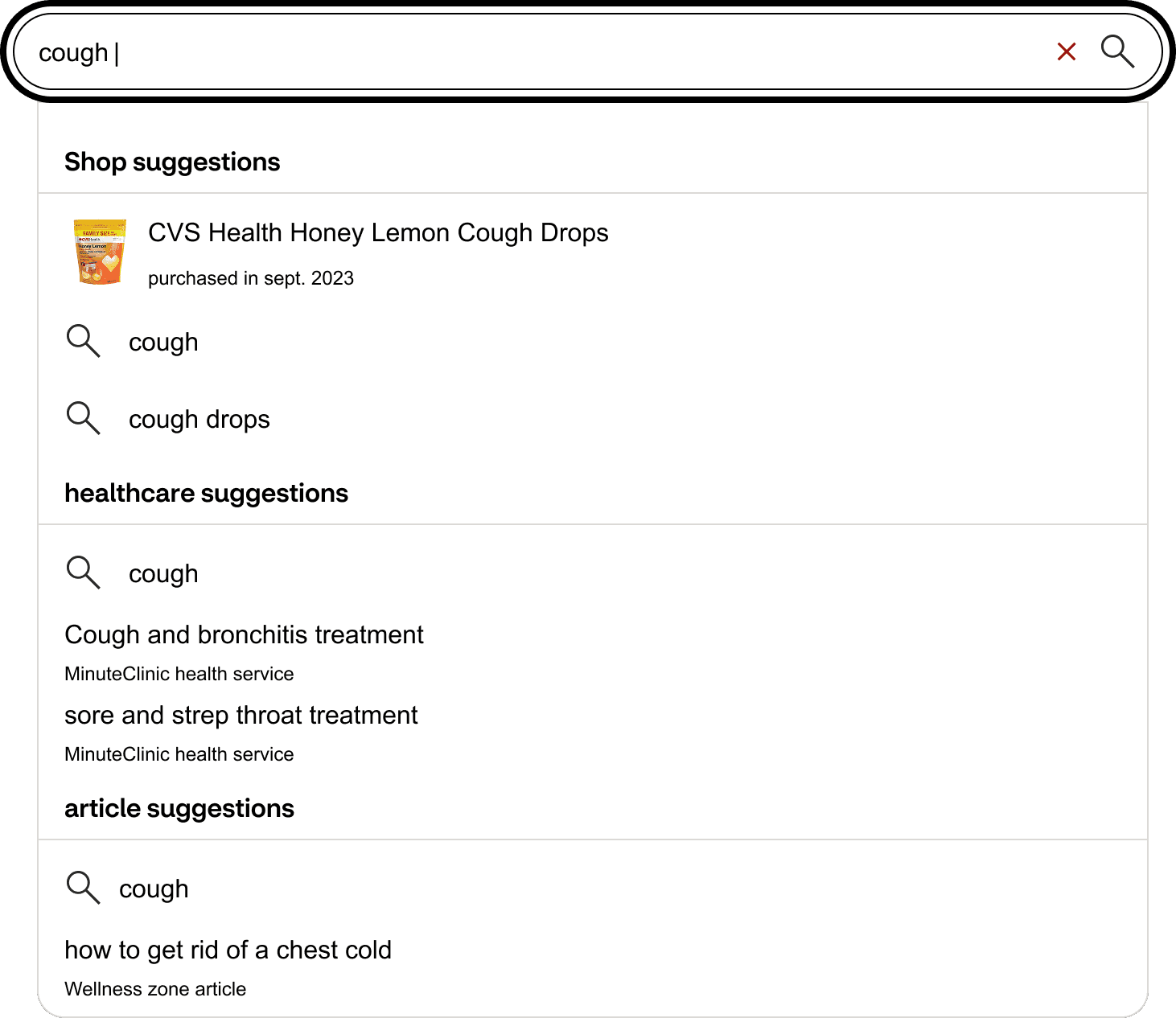

Cross-Platform Design Systems

After this typeahead project was finished, we began to shift our sites onto the mobile app versions of search. Our stakeholders wanted everything to look exactly the same across each platform, but this would be a subpar experience. No one is using 2 CVS apps and the website at the same time, its only in business meetings that we compare them all at once. It makes infinitely more sense to have each search experience provide the same content, data, and destinations, but each experience needed to feel like it belonged in that app and on that platform. We likened it like taking transportation modes to the same place. Driving a car and taking a plane to the same place are vastly different experiences, and a one size fits all approach whether you take a car or plane will result in a disastrous trip!

When Stakeholders were Right

Before: Cluttered, odd indents, and ineffecient use of real estate.

After: Cleaner, more list items, zero non interactive elements

My original designs included headings to help divide up the search categories. The effect was larger text that was non interactive, and it pushed down search suggestions. In our user research, we knew user engagement dropped off the farther down the list you look. Originally, I felt that this new search would be too complex if we were not explicit in our designs. However, thanks to stakeholder pushback, and frankly valid concerns over the real estate, I eventually landed on the subtext design. The subtext is significantly smaller, and part of an interactive element, meaning that the first piece of text users see in the searchbox is a suggestion. This was another instance where pushback led to a more elegant design, except this time it was my stakeholders who sent me back to the sketch book.

Launch & Results

Throttled Rollout

After annotating our designs and handing off to our developers, it was time to launch. We wanted to monitor the impact on our already revenue-generating search, as now some suggestions and direct links led to information pages. As such, we throttled to 10% of users each week over 10 weeks. This was a smooth deployment process with minimal issues, ensuring that existing functionality was protected while expanding to tens of thousands of users every week.

Metrics That Exceeded Expectations

I'm confident in my design skills and business acumen, but I was genuinely shocked at the results. Navigation to most of these pages, outside of the pharmacy services, was very low due to a cluttered navigation and sub-navigation experience. A 600% increase was more than I expected, let alone a 2000% increase. Furthermore, Wellness Zone also saw a great amount of engagement, which had virtually no traffic previously. Outside of an external Google search or combing through the sitemap, there was no way to access the few articles that were live before our search. This validated that search can drive massive traffic to new or obscure parts of our site. My manager refers to search as the backbone of the site and these numbers proved it. Not only are we the backbone, but my designs also prove that multi-database search is the answer for large corporations with complex offerings.

Lessons Learned

Simple and clean design is almost always the answer for enterprise businesses. While I could have reinvented the wheel and forced users into asking a chat bot questions, I believe that when users are searching, they're already distracted. They want to get to what they're looking for. I learned this very early on, but I still was amazed at how predictable and scaleable designs can be remarkably simple. This simplicity, in a task driven environment, when our users may be multitasking, was our superpower.

By focusing on small wins at first, and armed with a lot of patience, we unlocked massive potential. Not only did I prove my value to my partners and myself, but I also demonstrated that search can be a navigational tool. For too long has search been a tool to sell products on large enterprise sites, now we can bring CVS offerings right to our users fingertips. Although it took rounds of testing and many iterations, the design was not the hardest part of this project. It was staying the course, while some stakeholders and leadership seemed hellbent on making an impact by essentially redoing all our work.